Chapter 21: You Have One Doubt, They Call It Treason

In which I take a look at the revolutionary early years of Roberta Flack's career, and get dubby with McD's Dagger.

Happy Saturday!

This chapter was supposed to reach you a couple of days ago but, as ever, tempus has been fugiting, and once again I must apologise, both for my tardiness AND my flagrant disregard for ancient latin. This last week, if you follow me on social media, you’ll no doubt have seen me endlessly sharing the article I wrote for The Quietus to mark the 40th anniversary of the Sleng Teng rhythm, which isn’t exactly the 40th anniversary, but you’ll have to get comfy for a long read if you want to know what that’s all about.

I’ve also made another illicit dub track, and this time I’ve dabbled in dubbing something beyond the world of reggae, taking my razor to the downbeat jazz-funk oddity that is ‘Jagger The Dagger’ by Eugene McDaniels. There’s a clip below, but if you’re a full subscriber, or would like to become one for a fiver a month, then head to the bottom to grab it. But before that, I’ve written (quite) a few words about McDaniels and his close friend Roberta Flack…

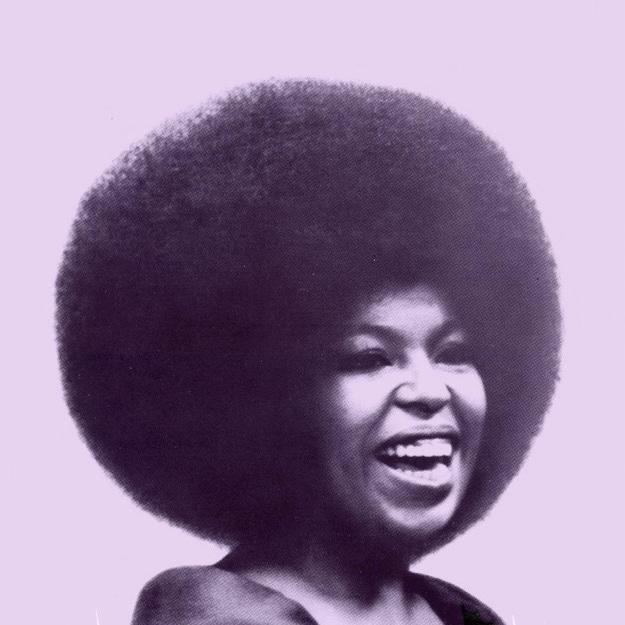

Another day, another death announcement across social media. In fact it’s been a miserable week if you’re a soul/jazz/folk fan. On February 20th we lost Jerry Butler from the Impressions. The next day it was Gwen McCrae and Bill Fay, followed by the news of reggae veteran Ken Parker on the 22nd, and honorary Isley Brother Chris Jasper on the 23rd, but the one which hit me hardest was Roberta Flack who’d been battling ALS for a while when she passed away a few of days ago.

In the early 80s, long before my days of vinyl-gathering, Roberta Flack was just a name which would pass by in the background. A gentle voice floating over smooth 80s ballads, or on jazzy latin-lullabies with an easy-listening aesthetic. Sometimes, while flicking through a box of dog-eared Bert Kaempfert and James Last albums hidden behind rails of tatty old charity shop clothes, I’d stumble on Flack’s Killing Me Softly album, fiddling with the fold-out piano on the cover (if it happened to still be in one piece). What soulful treats hid behind these cardboard layers, I didn’t know, because I would always leave it in favour of something more kid-friendly, like discarded Star Wars tat or a Peanuts book. I took a punt on a few silly records now and then, but the habit hadn’t quite hit me yet.

I was fully struck down by this musty-vinyl malady in my teens and, in the autumn of ‘91, having placed a crisp fiver from my first Saturday job on the counter at Collector’s Records in Kingston, I bagged a copy of First Take; Roberta Flack’s first LP, my first Roberta Flack LP, and it soon became the first LP on a list of my favourite LPs by anyone, ever.

That’s not an exaggeration, it’s stunning; from Flack’s opening piano chord on ‘Compared To What’ to the closing fermata during which she holds the final line of ‘Ballad Of The Sad Young Man’ for a devastating 10 seconds. This wasn’t the easy-listening schmaltz I’d imagined at all, but eight tracks of raw, yet beautifully executed protest-soul, performed over a sparing jazz backing, informed by folk, gospel, classical and even bolero. There’s a visceral quality to the recording, as if you’re there with her in the studio, feeling every stroke of the piano keys, or the tapping of fingers on the bass strings, the fingers of “my man, Ron Carter” on the bass, to quote Q-Tip on The Low End Theory, another album I picked up around the same time as First Take.

Like Flack’s album, The Low End Theory remains an all time favourite. A massive leap from their (already great) debut, which delved further into the realms of hip hop as the new jazz — “my pops used to say it reminded him of be-bop” — and much like Q-Tip’s pops, I remember my mum’s ears pricking up when she heard the rapper’s dulcet tones announcing the presence Ron Carter, as his bass notes folded around a rigid loop of Jim Madison on the drums.

Jazz samples and references were nothing new in hip hop, of course. ‘Jazzy Sensation’ and ‘Doing The Do’ both dropped almost a decade before The Low End Theory, while Gang Starr riffed on ‘A Night In Tunisia’ for ‘Words I Manifest’, and Stanley Turentine’s sax drifted behind the beat on ‘My Philosophy’ by BDP. Both hit the shelves before Tribe’s debut album, but somehow, perhaps due to Tip’s butter-smooth delivery, A Tribe Called Quest owned this new jazz-rap idiom.

It’s also Tip’s thing for jazz-funk obscurities which set Tribe apart. Their first LP, People’s Instinctive Travels And The Paths Of Rhythm featured layers of lush jazz, and loose funk breaks, appropriated from the likes of Billy Brooks, RAMP, Lonnie Smith and Les McCann. But it’s a mysterious beat which fades in at the end of the head-nodding jazz-noodle of ‘Push It Along’ which caught my attention.

I can’t remember when or where I first heard ‘Jagger The Dagger’ by Eugene McDaniels in full, such was a time before online databases which drag back the curtain of sample-wizardry, but I’d assume it was a friend with more money than I could mustre for McDaniels’ long out of print Headless Heroes Of The Apocalypse album. Eventually I found it — a crackly copy for £20 in Ray’s Jazz Shop, if memory serves — and an obsession quickly manifested.

McDaniels is probably still best know for a stack of soul hits throughout the early 60s including ‘100 lbs Of Clay’, ‘Tower Of Strength’ and even a cover of ‘Green Door’ two decades before Welsh rocker Shakin’ Stevens knocked ‘Ghost Town’ off the top of the pops during a summer of civil unrest. To tell the truth I wasn’t that familiar with McDaniels’ early output, though I had watched him perform ‘Another Tear Falls’ in Richard Lester’s It’s Trad, Dad! from the days before Lester struck gold with a brace of Beatles movies.

In fact the musical invasion of America by the Fab 4 and the Stones in the mid 60s was a tipping point for McDaniels who turned his back on smokey nightclubs, and stepped out of the spotlight to focus on selling songs to other artists. Ploughing what little earnings he still had into the seeds of a publishing business which rinsed him of his final dollar, McDaniels wound up sofa-surfing, even sleeping in Washington Square Park in NYC for a few nights. He desperately hoped to get the first of these new songs into the hands of his old friend and ex-bandmate Les McCann. “When I wrote this song, he was in my mind,” explained McDaniels in a candid video in 2010. “But, the caveat is,” he continued with a chuckle, “Les and I were not speaking at the time!”

Luckily, Les recorded it, and McDaniels first protest song ‘Compared To What’ debuted on the 1966 album, Less McCann Plays The Hits, alongside latin-jazz standards including ‘Summer Samba’ and ‘Guantanamera’, and even a cover of Donovan’s ‘Sunshine Superman’. It would take another three years to actually become a hit, however, when McCann performed the song at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1969. Atlantic released the set as Swiss Movement, deeming ‘Compared To What’ good enough to receive a heavily truncated single release, and soon McDaniels received a call declaring his song “the number one jazz tune in the world!” Not bad for a first attempt at a publishing endeavour, and even more so considering it was a song inspired by “the right wing push toward globalisation and privatisation.”

A few months prior to Montreux, McCann chanced upon a show at Mr Henry’s nightclub in Washington DC where the Roberta Flack Trio held down a residency. It was a benefit gig for the Inner City Ghetto Children’s Library Fund, and McCann was stunned by Flack’s performance, later writing in First Take’s liner notes that “her voice touched, tapped, trapped and kicked every emotion I’ve ever known.” He swiftly arranged an audition with Atlantic Records who inked a deal and booked her into the studio with seasoned jazz veterans including the aforementioned Ron Carter on double bass.

But while this might sound like the story of McCann discovering a jazz wunderkind, Flack was 32 when she entered Atlantic Studios to record First Take, some 17 years since she skipped out of high school to begin her university career as a piano virtuoso at just 15 years old. Since the early ‘50s, she’d been performing classical, gospel and pop alongside anyone from opera singers to club bands, eventually being urged to sing herself, so she’d honed her skills considerably by the time McCann got her through the door at Atlantic, and introduced her to McDaniels’ composition, ‘Compared To What’.

When McCann performed the song with his degenerate growl over a riotous latin swing, it almost betrayed the agitprop themes in McDaniels’ lyrics, but under Flack’s spell, it morphed into a rolling jazz-funk rhythm which contorts and expands with every verse, the weariness in Flack’s voice echoing McDaniels’ frustrations with the world. These were Gene’s words, but Flack embodies every line with a fearful trill, and as infectiously danceable as it might seem, the song feels like a final gasp in the face of defeat. An odd way to kick off a recording career, perhaps, but this wasn’t a young starlet, hungry for the spoils of fame, and McDaniels’ next step would be even less commercially viable.

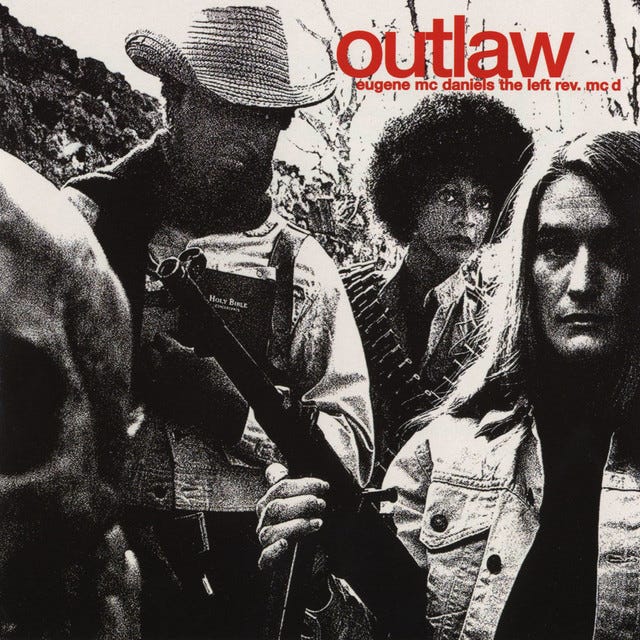

While Flack was making her Chapter Two LP, McDaniels co-opted the First Take rhythm section to assist with what could ostensibly be considered his 10th studio album, but it makes more sense as the debut of The Left Rev. McD.

Via the Flack-McCann connection, McDaniels signed his name by the X on Atlantic-headed paper, and set about recording Outlaw in 1970. Gone were those silky tones and sharp suits of the early 60s, replaced with distressed denim, unruly facial hair, and a desperate wail, as the Left Rev spat sardonic rhymes about nervous breakdowns, the ill-gotten gains of war, and penned a ‘Love Letter To America’; “you could’ve been a real democracy, you could’ve been free”, he laments on the latter. It’s a surprisingly country-infused affair, with just enough jazz-funk to keep the Atlantic fanbase happy; when McD isn’t rapping about “the skeletons of blood-stained hands”, of course, and it tickles me to imagine Atlantic’s Ertegun brothers shifting uncomfortably in their executive seats as he screams “SPEAK YOU NOT OF GENOCIDE” to the melody of ‘We Three Kings’.

As you can imagine, it wasn’t a huge seller, in fact neither was First Take, nor Chapter Two, or even Flack’s third album Quiet Fire when they were first released. Though Flack garnered a growing fanbase amongst jazz and soul fans, these records were perhaps too introspective to cross into the mainstream, and definitely on the wrong side of black power for the pop charts at the turn of the 70s; Ms Flack was too black, too strong. Like her debut, Chapter Two opened with the McDaniels-penned number, ‘Reverend Lee’. “A song about a very big, strong, black, sexy, southern baptist minister”, declares the singer, moments after the needle drops on side one.

‘Reverend Lee’ also appears on McD’s Outlaw, but in place of Flack’s coquettish intro, we hear tortured screams and a devilish cackle as the sexy reverend succumbs to temptation over 30 seconds of free-form jazz. Gene once stood shoulder to shoulder with titans of soul such as Marvin Gaye and Sam Cooke, but as McD he had more in common, sonically at least, with the satanic jazz-rock of Black Widow.

The title of his follow up, Headless Heroes Of The Apocalypse, and the fuzzy portrait of the singer screaming on the cover, probably didn’t do him many favours either, but the contents was a far funkier affair, leading Pete Rock, Eric B and The Beastie Boys to all lift loops from the title track, and of course, as mentioned above, A Tribe Called Quest used the intro of ‘Jagger The Dagger’, a track which appears to pass judgement on the Stones’ frontman who had just recently written the ill-advised* ‘Brown Sugar’, with McD and his Welfare City Choir’s voices drifting into almost atonal territories at the end of each staggering verse. It’s wild when you first hear the vocal drop where the Tribe loop ends. A far cry from the daisy age of the Native Tongues crew, but perhaps the horror-core of Gravediggaz’ ‘Nowhere To Run’ is more in keeping with the source material.

What neither McD or his label were expecting was a call from the Whitehouse. Despite it’s commercial inaccessibility, Headless Heroes Of The Apocalypse had caught the attention of the Oval Office, no doubt due to its uncompromising content aimed squarely at the Nixon administration, and soon Vice President Agnew was on the blower to the Ertegun brothers, demanding Atlantic drop McDaniels, or presumably face the consequences.

Meanwhile, Flack had a surprise hit on her hands thanks to, of all people, Clint Eastwood who licensed ‘The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face’ for his directorial debut, the psychological thriller Play Misty For Me. Flack almost said no, but Clint convinced her, and Atlantic seized the opportunity, releasing a single some three years since it was recorded. The lady who was discovered in her 30s playing at a fundraiser for inner city libraries was now at number 1 across the States, Canada and Australia. She made it to 14 in the UK in the summer of ‘72 as the Stones drifted off the bottom of the charts with ‘Tumbling Dice’. Baby, they couldn’t stay.

Ms Flack was now a bonafide star. The single won her song of the year at the Grammys in ‘73, then she won it again for ‘Killing Me Softly’ the following year. But despite her new found fame, and McDaniels’ now-unbankable aura, she still performed his songs, including ‘Rivers’ on the Killing Me Softly LP, and the title track from her 1975 album Feel Like Making Love. It’s hard to imagine the latter was penned by the same guy who once yelled “THEY’RE SLITTING OUR THROATS RIGHT IN FRONT OF OUR EYES” on ‘Headless Heroes’, but McDaniels was a man of many guises and by the mid 70s he was entering his romantic disco period, while his good friend Roberta embraced her status as a household name.

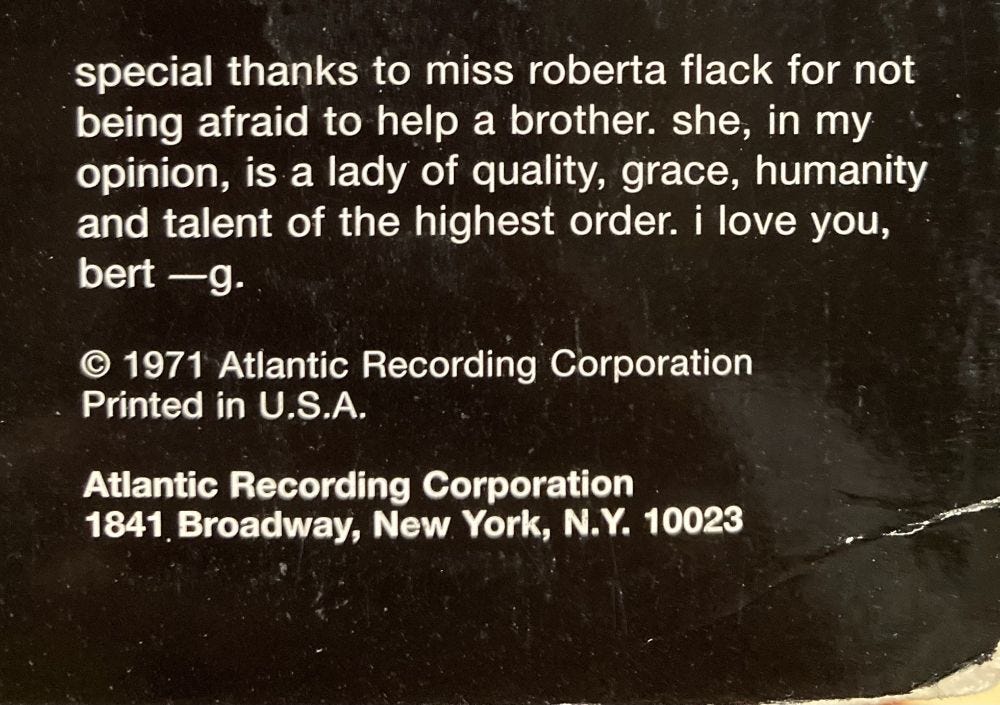

Eventually Flack and McDaniels would traverse their separate paths, but for a few years, from the moment Flack reimagined ‘Compared To What’, the pair shared a tender friendship, supporting each other when times inevitably got tough for a couple of left field thinkers in an industry of record sales and billboard charts. Testament to which, the only thank you on the back cover of McD’s Headless Heroes Of The Apocalypse is a heartfelt dedication from “G” to “Bert”.

*I’m being charitable here, Jagger’s lyrics are quite vile.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dubstack’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.